Why we don't get complexity: Stafford Beer, 'requisite variety' and systems thinking

In which I explore ways in which we can navigate complex adaptive systems

In the past couple of posts, I’ve used a metaphor for evolution as being equivalent to pushing on doors (trial and error) and storing learned pathways as codes, rules, practices etc;

This week, I read a fascinating political discussion on an adjacent topic from

(@conspicuouscognition), in which he contrasts the views of Walter Lippman and John Dewey on (paraphrasing) how politics should handle the ‘ignorance’ of voters. Here’s an example:More specifically, in ‘Public Opinion’ (1922), Lippmann argued that the modern world is too vast, complex, and inaccessible for ordinary citizens to acquire the political knowledge that democracy demands. Given this, he argued that much more power and influence should be assigned to a class of technical experts capable of overcoming citizens’ limitations.

Today, I read a separate, and also interesting essay by

, this time discussing ‘cynernetics’ as the possible ‘science of the polycrisis’. In this post, Farrell harks back to well received book about Stafford Beer and his extremely interesting ideas regarding the ‘attenuation of requisite variety’.Cybernetics is about feedback loops - providing information back to the system about how things are working or not working, whether the environment has changed and such.

What these posts have in common is that in both cases they are asking how we manage complexity? How do we simplify and adapt and stabilise without authoritarianism or even fascism. In the first post, this problem is presented as the paradox of the democratic process in which unskilled humans are asked to lend their vote to complex political strategies about which they know nothing. Williams is concerned that this opens the door to simple storytelling by populists. Meanwhile, Farrell concerns himself with the problem of ‘fixing’ the sprawling, complex labyrinthine mess of US public services. This week, the narcissist-in-chief has resolved this in a SIMPLE way - break them, then see if anything continues to function.

Rather than litigating these posts, I feel that readers would be well served with a simple introduction to complexity. So I’m going to try and give you that here:

A complex system is one in which parts are recombined to create lots of different things. A complex adaptive system is one in which parts can self-organise to create lots of different things that help them survive better in their environment.

This is RULE NUMBER 1 of systems thinking. Parts combine to make new things.

RULE NUMBER 2 of systems thinking is that parts come together at different space or time scales (leaf, tree, forest, ecosystem, planet etc;)

RULE NUMBER 3 of systems thinking is that (emergent) pathways (from recombination of parts) become more complex over time. (This is because they have to go through more ‘doors’).

RULE NUMBER 4 of systems thinking is that we can look backwards at the doors through which we have passed (if they have been codified into patterns, knowledge, textbooks, rules etc;) but it is really hard to look forwards.

RULE NUMBER 5 of systems thinking is that systems pivot around stable attractors - until they don’t. (Note: I can’t go there with attractors. Please read James Gleick’s book on Chaos, beat your palms mindlessly against a wall and come back in 5 years. That worked for me)

OK, enough rules for now. Let me try and explain this as a story:

Once upon a time, some people came together and created a little tribe (Rule 1). This tribe adjusted to its environment through trial and error learning. As it learned, it laid down rules, norms, habits and eventually technology (language, debt, food production etc;) (Rule 3). This meant it didn’t have to keep reinventing the wheel (very efficient!). The tribe could just follow prior learned patterns. The longer the tribe existed (Rule 2), the more complex these rules, technologies, norms etc; became (i.e. the more doors were opened and the deeper the pathway). The tribe was very successful and reproduced itself in large numbers. Thanks to all the early trial and error learning, the environment was stable with well-understood characteristics. The patterns of tribe members’ lives revolved around these stable characteristics (the attractors). The tribe became bigger and turned into a civilisation thanks to an open door policy towards new ideas (Rule 3). But as time passed, small changes in the outside environment (butterfly effect) meant the apparently stable patterns were subtly changing. Nobody noticed this to begin with. They responded to all novelty (variation) by applying the same rules and patterns that had worked before. These were controlled by priests (technocrats, experts) and there were sanctions for ignoring them. When a new tribe appeared on the hill, they applied the old rules. Unfortunately, the old rules lacked the ‘requisite variety’ to counter the novel threat. The patterns had changed and nobody had noticed until it became a crisis. The civilisation collapsed (Rule 5). Thousands of years later, experts explained all this as if it were SIMPLE and predictable (Rule 4).

Complexity is about trying to understand the future. Simplicity is about trying to understand the past. Experts / technocrats and historians are very good at understanding the past but not so good at telling us about the future.

In truth, it’s not really fair to call interpreting the past ‘simple’ but it is simple in the sense that it is knowable. If you can dig deeply enough, you will find out what happened in the past (sidenote: this is where AI is going to quickly unearth a lot of stuff buried in our collective cultural brain). The thing that happened in the past will not change. Because the arrow of time does not run backwards, the system is effectively closed and has a finite action space (the action space is the lattice or set of doors that I have used as a metaphor for evolution in previous posts). So historians need only grapple with interpretation, not evolution.

Complexity, meanwhile, is different. I have no idea if a car will crash on the road leading to my house this afternoon. It has only happened a handful of times in my time living here. So I can make a probabilistic prediction that there’s a less than 0.1% chance that it will happen today. But it might. Whereas I can guarantee that my house, built 500 years ago, will not self-organise into a cruise ship as I sleep tonight. It is not an adaptive system.

Now, Stafford Beer wanted us to understand systems so that we could better manage variation. Variation is just a fancy way of saying: change. Or novelty. Or difference. Or stuff that doesn’t fit the learned patterns, rules, technology etc; Unfortunately for 2025 humans, this discipline was christened cybernetics, a term later appropriated by science fiction writers and information technologists to describe anything digital.

This is annoying because cybernetics just means steering of a system. So if we stop calling it cybernetics and call it ‘co-ordination’, we might be more able to wrap our heads around it.

When a stable system experiences variation it must adapt or die. This is such an important point that I am going to call it RULE NUMBER 6. Evolution has developed a toolkit to help organisms do this. Many involve RULE NUMBER 1 (parts recombining). We tend to call this ‘co-operation’ and dismiss it as rather flimsy and weak. It isn’t. Recombination of parts / coalitions / co-operation are how we went from being bacteria to big-brained, complex apes.

According to Stafford Beer, the key to dealing with variation is to meet it with an equal and opposite amount of variation (the law of requisite variety). Controlling variation is described as ‘variety attenuation’. Beer believed this could be achieved through managing information flows. Political scientists have seized upon this as a possible solution to the polycrisis but they have, I fear, missed the essence of systems thinking. Information flows are indeed an ingredient in reducing variation but not as a single instrumental device. They are better understood as a way to connect local parts with a cybernetic (co-ordinating) centre. The point about ‘requisite variety’ is that these parts need to cover enough decision space or action space (the lattice from my earlier posts) to attenuate the novelty.

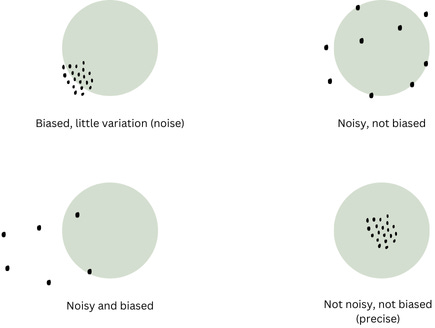

Daniel Kahneman has an interesting way of conveying this that is appropriate to this discussion. In his last book, written with Cass Sunstein, he discusses informational noise. Noise is really another word for variation. Kahneman provides a useful diagram which I have tried to replicate below, which explains this.

Imagine each of these circles represents a group prediction or decision about something novel. As Kahneman explains, some predictions may lack variation but cluster around a viewpoint. In this case, the group is biased. Other predictions may be noisy, but lack bias. Others may be noisy and biased and some may be precise (not biased, not noisy).

How does this help us attenuate variation? Experts occupy the first circle. There may be little variation in their view of a problem but they can still be biased. The voting public occupies the second circle - these are the people that Dan Williams worries about - their views are untutored and hence noisy. Social media opinions are often both varied and biased. They are not attenuating the complexity of the topics under discussion with requisite variety (because they are influenced by a few biased sources). Meanwhile, perfectly calibrated humans occupy the fourth circle.

So where do we find these perfectly calibrated humans who can predict the future? Well, Philip Tetlock believes there is a class of super-humans who are precise and lack bias thanks to particular personality characteristics. These include shifty, hard to pin down traits like:

listens to a lot of opinions

works in teams

reads around a lot

Hmm. I’m not sure how Tetlock tests these traits without some kind of self-select questionnaire so I’m not sold on the reliability of his construct. But the essence of what he’s describing is that a group of non-specialists with certain characteristics may be able to cover a wider decision space than a bunch of biased experts. And if you don’t have a talented group of what Tetlock calls superforecasters to hand, then what? The answer lies in the right hand side circles. You get MORE opinions. This is a pure wisdom of crowds problem. If you need to attenuate variety, you take more readings from the surrounding sensory system. And this is RULE NUMBER 7 of systems thinking: system parts have local and central elements.

The local bits of a system cover the further reaches of decision or action space (the lattice). They serve the customers, drive on the broken roads, experience the poor crops, see the storm coming, run into the burning building etc; They are the central nervous system of your cybernetic (co-ordination) engine. Experts sit astride the tiller but if all the local parts are screaming “turn left!”, then the tiller must be wrested from the grasp of experts and put into the hands of the wise crowd.

Remember in my original Traitors analogy, I explained how contestants moved through a series of (trial and error) doors to receive a prize? To teach others which doors to use, this system needed good information flows. Here, the local parts (each team trying the doors) yelled back their findings to the cybernetic centre (the remainder of the group who sought to maximise overall group performance). This is what Stafford Beer means when he says that variety can be attenuated by good information flows. Local parts (or nodes) that are close to the source of novelty (or variation) transmit back what they have learned to the centre (species, group, higher level scale of organisation) which adjusts its path (decisions / choices). This is adaptation and it’s how organisms, economies and civilisations stave off collapse or extinction.

The problem as oft stated, in modern societies, is that we have passed through many doors at breakneck speed and our institutions, norms, culture, technology, language and above all, brains, have not caught up. I am fortunate enough to spend a lot of time reading, but even making space for a few hours every day, I could not get myself to the level of an expert in a single discipline. This is a problem because it’s only the recombination of disciplines (rule number 1) that helps us see things differently. This is why all our learning has to be condensed into rules, codes, norms, practices etc; To put it differently, knowledge has to be ‘shouted back’ to us in some form that will help us adapt and respond effectively in our decision space.

In Dan Williams’ post, the decision space is political choice. Should we allow unskilled, non-expert citizens to make choices about ‘big, important things’ about which they have little knowledge. Surely, it is argued, such decisions should be made by a skilled priesthood who have passed through all these doors and have learned the ‘correct path’? Or by Dominic Cumming’s beloved superforecasters? Well yes - except the lattice (pathways) is multi-dimensional. It operates in time and space (Rule number 2). This means it can change size, change orientation, change speed. If this happens, the cybernetic (co-ordination) branch may no longer sit in the centre of the decision space. To respond effectively to this novelty, the cybernauts must listen to the local parts (the nodes at the edges of the decision or action space) who are the first to feel variation in the system. If there is a paradigm shift (a chaotic phase shift) then all the doorways may be flattened and prior knowledge must be abandoned.

I apologise if this is all becoming rather abstract. I also now sympathise, very much, with the writers of the 3 Body Problem who have tried to turn this stuff into popular entertainment. Let me try and simplify with an example:

In 2019, a fire broke out in the roof eaves of Notre Dame cathedral. The Parisian fire brigade rushed to the scene and followed the usual rules for terminating a fire. (These rules represent the codes, norms, methods, technology etc; learned from many centuries of firefighting trial and error). But at some point in the fire, it became clear that following rules would not be enough to contain the fire. The firefighters faced novelty. By the way, novelty is very much par for the course in high reliability organisations (fire / nuclear / aircraft carrier etc;) hence they build in many resilient practices to cope with this (Karlene Roberts is the go to expert on this). Anyway, that evening at Notre Dame, the rules weren’t working. To use Stafford Beer’s language - there was not enough requisite variety in the rules, to attenuate the novelty (unexpected, emergent problems). Or to put it another way, the firefighters found themselves in the top left hand circle of Kahneman’s noise examples. The cybernetic centre (the leadership / co-ordinating group) had closely bunched views on how to proceed (all the rules from prior trial & error learning) but these rules were not covering a wide enough decision space to attenuate the variety / put out the fire. A good team of cybernauts does the obvious thing as this point: it gets MORE viewpoints. And it gets these views from people exposed to a broader decision / action space. Literally, it means speaking to people who are close (local) to the problem or source of novelty. There is a great Storyville documentary on this. I urge you to look out for the scene in which the fire chief convenes a varied group of people (including frontline firefighters) to explore adaptive strategies. It is a model of leadership in a crisis.

I have laboured over this example but I hope you will have picked up some important takeaways:

Complexity (of learned pathways) can be collapsed into rules, codes, methods, practices and technology

Information about these learned pathways (the rules, codes, practices and technology) must be shouted back (information flows, training, learning) to the rest of the group / organism

If experts / technocrats / priests control everything, they can only cover a narrow decision space based on prior trial and error learning (known as path dependence)

Their views may be precise (Kahneman’s fourth circle) at times of stability

But where there is novelty or variation, the decision space may change shape

When this happens, the priesthood's earlier precise views will shift from the centre of the decision space. Now they are biased

And so, they must use local parts to broaden their understanding of the new decision space

And then, trial and error learning must recommence

Great cybernauts (co-ordinators) understand complex adaptive systems so this is intuitive for them. But it’s not intuitive for most people. Henry Farrell (whose post covered the problems of moderation on social media) is honest enough to say that it’s not intuitive for him. It is also abundantly obvious that none of this is intuitive for political leaders. When faced with novelty or variation, their tendency is to tighten control from the (biased) centre, rather than loosen control and widen understanding of the decision space (the lattice). Corporations espouse ‘agile’ policies while being clueless about what this really means. It is not a Kanban Board and a couple of beanbags. Aside: I would sell one of my children to see the look on Stafford Beer’s face if confronted with a corporate ‘agile’ delivery approach. Truly adaptive behaviour is a mindset.

Which brings me to Donella Meadows.

Donella Meadows was a student of Jay Forrester, a very bright and interesting systems scientist at MIT in the 1960s. Forrester conceived of new ways to model big, difficult things based on feedback loops. Mostly when we model things, we take a snapshot (or at least, this was still the case when I was in the corporate world a few years back) of the action space. This would mean loading up a model with a set of assumptions and spitting out some scenarios. Forrester took a different approach. He would try to model the whole dynamic system, not a point in time. If one assumption moved (more / less of this), then everything in the model moved, dynamically. This is such an obvious way of condensing complexity that it pains me to see how little it is used in modern political and corporate planning. But of course Forrester (and before him William Edwards Deming and Stafford Beer) were about to find themselves eclipsed by a new paradigm - shareholder value. Who needed thoughtful, modelling of complex systems when you can reduce everything to hitting a short term profitability target? No matter the long term damage to the system, ecosystem, economy and culture in which that entity is nested?

Forrester’s approach was highly influential in the Club of Rome, Limits to Growth model. This model argued that current (1970s onwards) levels of growth (population and energy use) were unsustainable and would eventually lead to a systems collapse. This was, as many will know, widely criticised when launched. Over time, however, the model’s outputs have proved remarkably prescient. I don’t want to get into an argument about whether Limits to Growth is or was a useful model. But I do want to highlight that a systems approach to decision making would condense knowledge into tools and methods that allow people to scramble along complex trial and error pathways and reach the priesthood without the pain (note: AI can help a lot with this). Forrester himself, acknowledges the problems of human judgement. He proposed the use of dynamic systems models, with exposed assumptions, to allow people to make informed decisions (from his Wikipedia entry):

The mental model is fuzzy. It is incomplete. It is imprecisely stated. Furthermore, within one individual, a mental model changes with time and even during the flow of a single conversation. The human mind assembles a few relationships to fit the context of a discussion. As the subject shifts so does the model. When only a single topic is being discussed, each participant in a conversation employs a different mental model to interpret the subject. Fundamental assumptions differ but are never brought into the open. Goals are different and are left unstated. It is little wonder that compromise takes so long. And it is not surprising that consensus leads to laws and programs that fail in their objectives or produce new difficulties greater than those that have been relieved.

So we now have a set of propositions to help us navigate complexity:

Difficult, complex stuff should be condensed into rulebooks, technology and learning that can be shared as broadly as possible

But, decision space (the lattice) is broad and constantly changing (at different speeds - Rule 2)

And, this means stable, learned patterns will also change

Dynamic modelling of feedback loops may help us to imagine these changes and adapt our assumptions quickly

BUT, in any complex adaptive system, we will always need to keep listening to the local parts

Because, they will be the first to see (feel) the fire / enemy / storm (variation)

So, changing a system is not just about information flows (!)

Back to Donella Meadows. Meadows was the lead author of The Limits to Growth model. She thought in systems. In 1999, while attending a discussion about plans for global free trade, Meadows vented her frustration:

So one day I was sitting in a meeting about how to make the world work better — actually it was a meeting about how the new global trade regime, NAFTA and GATT and the World Trade Organization, is likely to make the world work worse. The more I listened, the more I began to simmer inside. “This is a HUGE NEW SYSTEM people are inventing!” I said to myself. “They haven’t the SLIGHTEST IDEA how this complex structure will behave,” myself said back to me. “It’s almost certainly an example of cranking the system in the wrong direction — it’s aimed at growth, growth at any price!! And the control measures these nice, liberal folks are talking about to combat it — small parameter adjustments, weak negative feedback loops — are PUNY!!!”

Meadows jumped to her feet and commandeered a whiteboard. Mindlessly, she banged out a list of 9 points to intervene in a system (extracted here in unedited form):

PLACES TO INTERVENE IN A SYSTEM

(in increasing order of effectiveness)

9. Constants, parameters, numbers (subsidies, taxes, standards).

8. Regulating negative feedback loops.

7. Driving positive feedback loops.

6. Material flows and nodes of material intersection.

5. Information flows.

4. The rules of the system (incentives, punishments, constraints).

3. The distribution of power over the rules of the system.

2. The goals of the system.

1. The mindset or paradigm out of which the system — its goals, power structure, rules, its culture — arises.

Notice that information flows is only listed at number 5. Top of the list is mindset. Any complex adaptive system that is run according to a paradigm that conflicts with system goals, is going to fail. So when

asks how to respond with sufficient requisite variety to misinformation on social media, I would answer that information flows are pretty far down the list. At the top - and the most blindingly obvious one - is the mindset or paradigm out of which the system arises. Stafford Beer’s (now) famous acronym was POSIWID - the purpose of the system is what it does. The purpose of social media is to monetise emotions into income streams. Informing people that their views are biased and imprecise - even offering them information to explain this - is unlikely to change behaviour if the system is set up to reward bias, imprecision and emotionally salient content. Meadows’ points 2-4 just reinforce this. If the system’s goals, rules and distribution of power are all aimed at rewarding imprecise, biased content then good luck telling people not to use it! Eating a box of gelatinous, expensive, bacteria-infested pick and mix is objectively bad for me, but I still pigged out through The Brutalist at the weekend.In this post, I’ve developed some themes about systems thinking and laid out a few propositions as rules of thumb (heuristics / learned pathways) to help us navigate complexity. Stafford Beer’s work is indeed a fantastic resource, and his ideas can help us reorient our thinking. But if we compartmentalise this into simple tools of ‘more information flows’ or more corporate ‘kanban boards’ without seeing the WHOLE SYSTEM then we will fall into the same old reductionist traps. Asking Governments to increase information flows to participants in our democracies is a pretty good start, but none of that will be achieved without changing the mindsets, rules and goals of the system. To navigate a complex adaptive system, we must understand the action space in which we operate, and be humble about what we don’t know. Experts, technocrats and priests can tell us a lot, but we need the sensory feedback from all the parts of our system if we are to sense and adapt quickly to novelty.

As a final year engineering student I was developing models on an analogue computer to solve non-linear differential equations, reading amongst others a Jay Forrester book. Seems obscure even now. What stuck in my head were ideas of non-linearity, systems thinking, feedback loops - some of the basics of complexity and chaos. This was 55 years ago! For me the world has always been more non-linear than linear, complex rather than simple with emergent properties. However I’ve learned that for most people this is far from intuitive and deeply challenging. Even ‘bright’ people - especially accountants and economists - with rigid mental models. Meteorologists have understood this for decades as have environmentalists. A few economists get it with great work at Santa Fe. Failure to understand systems and complexity is a huge barrier to progress, be it environmental, economic or social. Maybe we should be teaching the basics in high school. It’s a whole different way of seeing the world.

"BUT, in any complex adaptive system, we will always need to keep listening to the local parts...Because, they will be the first to see (feel) the fire / enemy / storm (variation)" -- this reminds me of Hayek's "The Use of Knowledge in Society" for ex:

"If we can agree that the economic problem of society is mainly one of rapid adaptation to changes in the particular circumstances of time and place, it would seem to follow that the ultimate decisions must be left to the people who are familiar with these circumstances, who know directly of the relevant changes and of the resources immediately available to meet them. We cannot expect that this problem will be solved by first communicating all this knowledge to a central board which, after integrating all knowledge, issues its orders. We must solve it by some form of decentralization. But this answers only part of our problem. We need decentralization because only thus can we insure that the knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place will be promptly used. But the “man on the spot” cannot decide solely on the basis of his limited but intimate knowledge of the facts of his immediate surroundings. There still remains the problem of communicating to him such further information as he needs to fit his decisions into the whole pattern of changes of the larger economic system."

However Hayek claims that "in a system in which the knowledge of the relevant facts is dispersed among many people, prices can act to coordinate the separate actions of different people", and that in an increasingly complex system, the incentive structures created by reaction to changes in prices are a more effective mechanism than the ill-fated attempt to communicate information to a technocratic center node.

Of course I think this errs in its assumption of efficiency-maximization of resource allocation as the "only" guiding principle of societal organization, something which is captured in Polyani's concept of the "Double Movement" i.e. the reliable, endogenous societal reaction function we can expect against over-subjection to market-based organization. I suppose this reaction function in turn could be interpreted from a cybernetic point of view, i.e. dispersed participants transmitting information back to the central node of policy makers that effectively conveys "I don't like being subject to market forces." Dan Davies captured this well and succinctly here I think: https://backofmind.substack.com/p/the-only-message-the-channel-can